How we tested our new emergency medicine (EM) content

Doing impactful research with EM doctors

How do you go about testing new content for doctors? That was the first question that came to mind when I was asked to test our new emergency medicine (EM) content for EM doctors.

It’s a challenging question for any researcher, however what made this research unique is that the content we were asked to test was not marketing content, or functional copy, but a product in and of itself.

There were many more layers to what our medical editors were trying to achieve. They were looking to understand:

- How the new EM content can complement, support and enhance a doctor’s experience during emergencies

- How it helps doctors prioritize the assessment and care on the most critical problem, or recognize the need to ask for help from team members or specialists, and

- What mistakes they can’t afford to make

As our AMBOSS articles intend to cover a lot of different uses, such as diagnosing patients, treatment management, providing supportive care, and more, it was important for us to understand exactly what is, and how our articles are useful on a granular level.

This post will explain how we tested new EM content to assess if we met the needs of EM doctors with a new EM article —Approach to the poisoned patient.

I’ll go through my own experience developing our approach to content testing, including ideas and approaches on how to prepare (preparation is key), how to put yourself in the doctor’s shoes when you don’t have a medical degree, and how we applied all our preparation work to our analysis.

Creating a Content Testing Menu

Testing the new EM content was an exciting new project we hadn’t done before, and our medical editors naturally had a lot of questions. We needed to find a way to help them articulate their testing objectives, understand what tests could be conducted, and what they would get out of testing the content.

So I created a Content Testing Menu to give us a way of having a conversation with our editors about what exactly the research objectives were, and help them understand how we could achieve these.

What do we want to test?

Usage and use cases

- What are the top 5–10 things participants are going to do with this content?

- What are our EM participants’ goals?

- What does success look like for our EM participants?

Value proposition

- Does our value proposition resonate with our participants?

- Are the benefits called out in our participant’s language?

Information understanding and processing

- What do we hope participants will understand and remember from this content?

- Which parts of the information do we think participants will / will not be able to understand and process, and why?

- Do participants understand our names, functional descriptions and instructions for features?

What would be the best methodology?

Content-focused moderated remote usability testing (UT)

- Encourages participants to share any problems of issues they noticed with the content

- Determines whether a technical term makes sense to participants or if it’s just jargon and needs better explanation

- Evaluates whether users understood what they just read

Highlighter exercises during UT looks at confidence

- Literally used to highlight what content will make participants feel confident or uncertain, and helps compare results from multiple participants

- Participant highlights words or phrases that confuse participants or make them feel uncertain in red / pink, that participants like or makes sense in blue, and that makes it feel like we ‘get’ their needs in green

- Researcher then asks the participants to talk about what they underlined and why

Mini-interview at the start of the test

- Helps validate some assumptions what they may use the content for

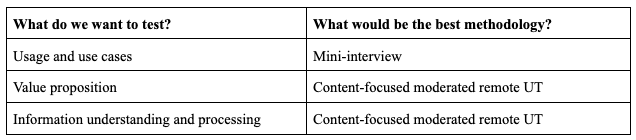

Once the questions were refined, I was then able to choose the appropriate method for our EM content testing. This was a mini interview to start, followed by a content-focused, moderated and remote usability test (there’s more about that in the crafting and testing the script section). The table below summarizes what we wanted to test and the chosen methodology.

How to understand medical content when you’re not a doctor

When you’re working as a researcher in an area where you’re not a subject matter expert, it’s really helpful to spend time with the experts to get a baseline understanding. This extra investment on the stakeholder side pays off in the quality of the research later on.

In order to test the content, you need to understand the content you’re testing. It’s not enough to just read the content, especially for a niche market like medicine.

I did this by asking our EM specialist and content writer for help. Our EM specialist created a document that outlined and explained the different ways in which:

- The content and product features appeal and respond to EM residents needs across all their different tasks

- The content is designed to complement, support, enhance the EM residency experience

- The specific objectives and use cases for each specific EM article as well as questions for each objective that EM residents may be asking themselves when with a patient

I remember reading one of the questions in the document our EM specialist prepared: “How do I keep this person alive while waiting for everything else to work?”

It hit me how fast our EM doctors have to act, and stay focused so they don’t miss anything! This document helped put myself in our participant’s shoes without needing a medical degree.

Crafting and testing the script

When crafting your script, I would suggest keeping it simple and to the point. Don’t overload the participant with specific questions that jump from one topic to the next, but rather respond to what the participant said by asking them to explain further.

As a fellow researcher, Nikki Anderson explained in her article about continuously improving research sessions: “I feel participant research is a bit like improv — you’re thinking on your feet, and base your next question off of what that person just said.”

I did a dry run of the script with our EM specialist before testing participants. This was helpful to practice this improv technique with this particular content, check if I could follow his responses (particularly all the EM lingo), and see if one hour would be enough time. I also asked our EM specialist for his feedback on the interview.

Lastly, we wanted to make sure our participants were in their first year of EM residency and had treated at least one intoxicated or poisoned patient. I created a screener survey to make sure we were recruiting the correct participants to test our content with.

The real test in both senses of the word

The aim of the mini-interview was to:

- Understand which resource(s) participants used

- At what point(s), and

- Why the resource helped them to care for their patient

By doing this mini-interview before the content-focused testing, I was able to ask the participants questions about specific parts of our content, that would likely have been relevant for their patient’s care.

For example, if a participant described how they performed a toxicological risk assessment on their patient, I used the participant’s description to ask questions specifically about our content on performing a toxicological risk assessment.

This structure gave me insights into what aspects of the content participants found important or helpful, what content they found confusing or question, and how this content compared to other resources they had used.

One of the tricky parts about content testing is timing your questions at the right moment. Participants need to have time to read through the content, and as the interviewer you have to learn to love the silence even more than usual. This is what makes content testing distinct from typical usability work on a feature.

To follow their thought processes while giving them enough time to read and absorb the information, I instructed them to think aloud as much as possible. Whenever they’d make a comment that was ambiguous, for example, “This is cool”, “This is helpful”, “I don’t think this is useful”, “Why is this here?” I’d ask them to tell me more or explain why.

Timing my follow-up questions was also very important. I didn’t want to interrupt their train of thought, but also didn’t want to let them get too far into another paragraph or section before clarifying what their comment meant.

Overall, we felt our content testing worked well as our technique gathered a lot of insightful and detailed feedback to analyze. Additionally, all the preparation we did beforehand certainly paid off.

Defining tags before analyzing is key

We’d gathered a lot of feedback about the different objectives and use cases our participants had come across, however, digesting this feedback was a mouthful. So I broke it down into smaller bite size pieces.

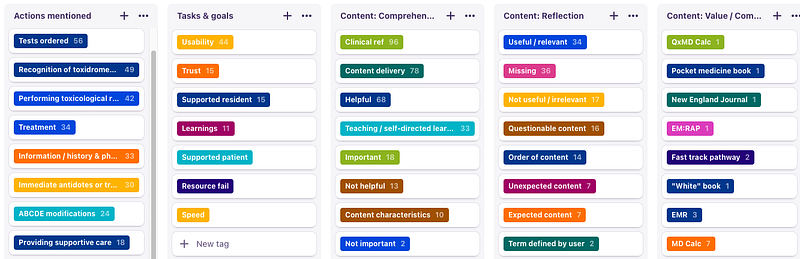

Using Dovetail, I created a framework of tags based on the document our EM specialist created and from our participants’ feedback. I first created tags for any tasks that were mentioned, for example, any immediate antidotes or treatments that were given to a patient when they were admitted to the emergency department or when they performed a toxicological risk assessment. The tags we used were based on the questions in the script and placed into categories.

Below is a screenshot of what it looked like when we put the information into Dovetail:

Using these tasks, I then created a table with the Actions mentioned that were cross-referenced with the other four categories. This helped to see the patterns and insights.

This is the first time I’ve prepared this type of complex tagging in this way, and I can honestly say it was incredibly beneficial for the project. We were able to classify the feedback on a deeper level, and bypass the usual tags (for example, wants, needs, haves, pain points) that haven’t often led to clear insights in a niche market, like EM residents.

If you try out this framework, I’d be interested to hear your thoughts, and if it worked well for you.

Conclusion

I learnt a great deal about how to prepare for testing content for a specialized market like medicine, and especially how content testing deepened my understanding of our participants’ daily lives as EM doctors.

One thing I would do differently is to get our editors more involved earlier in the process so they can observe the interviews and see first hand how our participants go through the content for the first time.

I also believe we underestimated the amount of insights we would gain from the content testing. We gathered a lot of feedback to analyze and disseminate across multiple teams, making this a bigger project than we initially anticipated.

When testing significant amounts of content for the first time that are meant to be consumed and applied in multiple tasks, be generous with your timelines. Let stakeholders know that feedback will take dedicated time to analyze and be shared with the relevant teams, to help set timeline expectations.

On a final note, this project showed me that with the right amount of preparation, successful content testing is achievable. I’d recommend this approach to anyone testing content on a topic or field that you’re not familiar with.

I hope you enjoyed reading this article! If you have any questions, feel free to contact me.